tv Wilson Center on Mexican Migration CSPAN November 6, 2018 9:33am-12:01pm EST

9:33 am

camden, newark, you know, these are cities that are completely run by democrats and they're, you know, they're very hard places to live. how do they concert the little accomplishment, if any, into these electoral successes in new jersey? >> remember a few things about my state. there are more democrats registered than republicans. it's a blue state. despite the first question talking about being purple. we haven't elect add republican to the united states senate since 1972, the longest streak in my state in america not to elect a republican to the u.s. senate so it's a tough state. now, what happens-- >> i would be curious if bob menendez, if you think he's in trouble. >> we can get to bob menendez. there's a pattern in new jersey, not one two term

9:34 am

democratic governor in years, but-- participating by c-span. i i'm wilson center's senior vice-president. today's event, mexican migration flows from great wave to gentle stream could not be more topical. i would like to thank the migration policies institute for co-hosting this event and i want to thank, again, everyone for coming out on this soggy day in washington d.c. it's not lost on us that we're holding this event on midterm election day, but i think having this event on this day in some ways feels appropriate, given that the topic of immigration, migration has been at the forefront of america's midterm elections. the flows of migration from mexico have reflected-- reduced from a great wave to a smaller stream. mexican migration to the u.s. is currently at net zero with

9:35 am

more mexicans leaving than coming to the u.s. yet being many americans have an outdated perception of what a mexican migrant looks like today. there are too few stories in the national conversation who is coming to the u.s. from mexico, how they bring meaningful contributions and what happens to their relationship with u.s. if they choose or are forced to return. this event, which is sponsored by the wilson center's mexican institute headed by duncan wood, as well as by the migration policy institute, aims to present information regarding the flow of mexicans both to and from the united states and explore the diversity and contributions that have been deeply a part of the united states. thank you for coming and now i'd like to present our distinguished opening speaker, the honorable ambassador gutierrez who is a friend of the wilson center and it's a

9:36 am

pleasure to welcome him back. he served as mexico's ambassador since 2017, previously served as managing director of the north american development bank, headquartered in san antonio, texas, where his professional activity was focused on infrastructure, development and finance along the u.s.-mexican border and previously served in prominent service in trade, finance, diplomacy under four presidents. and we're honored to invite him back to the wilson center. mr. ambassador, the floor is yours. >> thank you very much for that very kind introduction, good morning to all of you. allow me first to thank the wo woodrow wilson institute for organizing this seminar and for inviting me to be a part of it. these two institutions have

9:37 am

consistently made a very valuable contribution to our shared understanding of the migration phenomena between mexico and the united states and its implications. more importantly, both countries will always benefit from having a more thoughtful, open, and fact-based exchange of ideas about this topic. the seminar comes at a very fitting time. it provides a good opportunity to discuss the changes in migration patterns from mexico to the united states, and the diversity of more recent mexican migrants into this country and also, the dynamics and challenges that take place upon their return to mexico. all of these are very relevant topics to the ongoing cooperation agenda that mexico and the united states have and must continue to do so with respect to immigration.

9:38 am

as i've said before, mexico and the united states have a clear shared interest in working together to make sure that migration is safe, it's orderly, and it's legal. in my view, the it's clearly and simply unacceptable for everybody. and noll we achieve this objective, there will continue to exist a huge gap in the expectations and i dare say, the hopes that the governments and the people of both sides of the border have about the overall bilateral relationship. let me say this a little bit more bluntly. that during the current status quo clearly affects the tone, the substance, and the perspectives of the overall bilateral relationship.

9:39 am

during this morning's first panel, we'll hear about the changes in migration patterns. the panelists, i am sure, will give you a far more nuanced view of these changes than i can. however, let me just highlight what in my view is a single most important change. the sheer reduction in the number of mexicans that migrate to the united states. several studies and surveys, as well as the united states government's owner estimates point to this fact. mexican irregular migration into the united states quite clearly picked precisely at the turn of the century and since then, it has been pretty much in decline. today, unfortunately, it is often overlooked that the year 2000 register 1.6 million

9:40 am

apprehensions of mexican nationals by the border patrol in our shared border. 1.6 million. last year, 2017, that figure was 130,000. these numbers naturally invite the question of what has happened. what explains the change from a great wave to a gentle stream, to borrow the seminar's title? with respect to migration as another complex phenomena, i have learned throughout the years that one must look for multi-factor explanations. without a doubt, increased enforcement by the united states migration authorities is relevant and will continue to be so. but also, and i think more importantly, mexicans have found better opportunities in mexico during the last 20

9:41 am

years. years. but these numbers, at risk of sound of naive, this reduction, i believe, it's also important because it makes more likely than mexico and the united states could eventually find some form of agreed frame work to manage whatever migration and whatever mobility takes place between them. to put things in perspective, when the so-called whole enchilada was being negotiated or at least discussed 18 years ago, irregular migration from mexicans into the united states was an intractable problem and i do believe that it's no longer the case. during the second panel we'll learn about the face of recent mexican migration into the

9:42 am

united states, how mexican migration is becoming more diverse. using andrew's term in his book about the forces driving mexico and the united states together, there is a tsunami of mexican talent coming legally and enriching the united states as well as mexico. from farm workers to engineers, restaurant owners to computer coders, mexican immigrants reflect more and more the diversity and richness of the mexican labor force, as this schnarr program rightly points out. let's see these as an opportunity. as ambassador anthony wayne's recent research suggests, we have a skills gap that negatively affects our competitiveness and our economic performance,

9:43 am

understanding ours is that of the north american region. with the economy growing as it is, reports already show labor shortages in the u.s. in sectors such as construction, accommodation and food services and health and care, and social assistance among others. bring the demographics into the mix. the united states is precisely at that point when baby boomers are reaching retirement. the median age of the u.s. is 38 years, ranked around 62 in the world. the mexican median age is 28. rank about 133 in the world. so, yes, let's make it legal by all means. let's make it safe. let's make it orderly, and let me add, let's make it smart by

9:44 am

jointly thinking about worker force development for the future. the last panel will review the challenges and students that return migration presents. whether voluntarily or involuntarily, a significant number of mexican nationals return every year from the united states. it is important to understand why people return, what programs can be put together to make integration better, and how to take advantage of the skills and capital that migrants have acquired. as a global migration group points out, return migrants are potential drivers of development for their countries of origin if successfully reintegrated into the local society and into the labor market. let me conclude by saying as i mention, this seminar comes at

9:45 am

a fitting time. you're all aware of the lively debate going on about regional migration between mexico, central america and the united states. clearly there are no easy policy responses to regional migration trends that we're experiencing. as never before. in my view, we're facing nothing short of a serious humanitarian situation. and it only be addressed co comprehensively and definitely if, a, we continue to talk among nations of the region, and we continue to talk about the difficulties and differences. b, if we continue to address the development in those countries less fortunate presently and to be clear, aid from abroad to these countries will only be as useful as those

9:46 am

countries are willing to help themselves. and c, there needs to be enforcement of immigration laws throughout the region and we must do so humanely and roux inspect to human rights. and that we can address the present regional migration patterns that we're facing. i want to thank you again for the invitation to join you this morning, early. i again thank the migration policy institute and the mexican institute for educating our debate and our exchange of ideas about bilateral relationship overall. it has been, as i mentioned, a valuable contribution i've learned to appreciate throughout many years.

9:47 am

and i hope you have a good seminar and if i'll be happy to take questions if there are. and if not, i'll be happy to have my coffee. [laughte [laughter] >> thank you very much. [applause] [inaudible conversations] >> thanks again, everyone for being here, i'm rachel the program associate for migration and i'll be introducing our first panel we're excited to have. moderating at the end here is julia. she is a senior policy analyst at migration policy institute and works with the u.s. immigration policy program and her work focuses on legal immigration system, demographic trends and the implications of local, state and u.s. federal immigration policy. next we have mark hugo lopez.

9:48 am

mark is the director of global migration and demograph if i research at pew research center and leads planning of the research agenda on national demographic friends, international immigration, u.s. immigration trends. and we have a policy analyst at migration policy institute where he provides quantitative research support across mpi programs. his research focuses on the impacts of immigrant experiences of socioeconomic integration across varying geographic and political context. thank you. with that we'll go ahead and start. >> thank you, rachel, good morning, everybody. >> good morning. all right. again, good morning, thank you for being here in this what has been a wet start to a day. we appreciate that this is a topic as the ambassador mentioned that we will hopefully continue to engage in. this panel is meant to try to

9:49 am

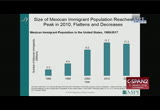

provide a background about what's really the trend and what's changing so we can have an informed discussion for further panels. so let's begin with-- actually as rachel mentioned, i'll be focusing specifically on immigrants in the united states. so let's start by looking into the numbers first. we know that the united states is, by far, the largest destination for mexican immigrants, but the phenomena of mexican migration to the united states is undergoing a significant change. after four decades of strong growth, the mexican immigrant population in the united states has hit a turn point in 2010. while the overall numbers of immigrants in the country increased 2010-2017. the number of mexicans flatten out and then into the decline in 2014. between 2016 and 2017 the mexican population shrunk by about 300,000 from 11.6 million

9:50 am

to 11.3 million and what you can see here in this chart is that not only the resents trends i mentioned, but go back to 1980 when the mexican population at its lowest point, 2.2 million that increased to 2.3 in 1990, 9.2 and 11.3 where we currently stand. i'll come back at the conclusion what we'll mention, it's important to know for a long time migration from mexico to the united states has largely been driven by low-skilled unauthorized workers seeking economic opportunity, but in recent years, the migration patterns changed due to some factors that the ambassador just mentioned. which include improving mexican economy, stepped up u.s. immigration enforcement and the long-term drop in mexico's birth rates.

9:51 am

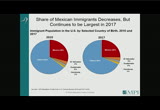

more mexican immigrants returned to mexico than migrated to the united states and apprehensions at the u.s.-mexico border are now at a 40-year low. in the second slide you can see that even though the numbers have decreased for mexican migration, mexicans continue to be the largest immigrant group in the united states. mexicans comprise 25% of the population compared to 29% in 2010. you can also see that for the countries of the northern triangle, el salvador, guatemala and honduras. and the key here is the change has occurred for, mainly for other countries, including some asian countries like china and india how increasingly taken shares of the u.s. immigration population. and again, this is 25% of the

9:52 am

44.5 million immigrants as of 2007 for mexico. where are mexicans residing in the u.s.? at large we know immigrants have been here for a long time predominantly located in traditional receiving states. we can think of california, texas, illinois. in 2006 period most immigrants from mexico lived in california about 37%. 22% in texas. and 6% in illinois. the top five largest metropolitan areas for mexican immigrants, los angeles, 1.7 of the total, representing 13% of los angeles population, chicago which is 650,000, representing 7% of the total pop leagues. hussein at 622,000, dallas at 613,000. and the riverside metropolitan area representing 562,000 mexicans. combined these five

9:53 am

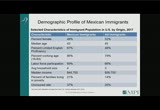

metropolitan areas make up about 36 or 37% of the total population of mexicans in the united states, just these five locations are more than a third of all mexicans. and you can see as well that there's also other regions that are maybe not traditionally immigrant receiving states, but, for example, you have washington state, oregon, also into florida and now more recently in the south, with georgia and alabama and other places, including louisiana that has seen an increase in mexican populations. so let's talk about, or at least for now, put the total demographic profile, what is similar and different for mexican immigrants compared to other immigrants in the united states. >> the first thing, mexican immigrants are more likely to be male. 48% female compared to 52% in the united states.

9:54 am

mexicans tend to be younger, 43 is median age for mexicans compared to 45 for all immigrants. and then there's also in terms of what we term limited english proficiency, which is the ability tore immigrants who speak english better than well, mexicans are about 63% of them are-- 67% are identified as limited english proficient compared to 48% of the total population and we can see that mexicans 86% of mexicans are within the working age range which we hear calls 18 to 64 compared to 79%. this is key the next point, which is labor participation for mexicans is 69%. that is compared to 66% of all immigrants, so mexicans are more likely to be in the labor force, and this is compared to 62% of the native-born population, so both mexicans

9:55 am

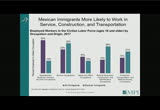

and all immigrants have higher rates of labor force participation. households of mexicans four people compared to three this total. median income about $45,000, compared to 56,000. and the percent of mexican families living in poverty is 21%, compared to 14% for all immigrants. uninsured rate for elk had, 37% of mexican immigrants lack insurance, compared to 20% of all immigrants. >> now, we've, i think, known for a long time that mexicans are an inter-- integral part of the labor force in the united states. what type of work they do. by the graph 29% of mexicans work in service occupations, 26% work in construction and other service occupations. and about 21% work in transportation and material

9:56 am

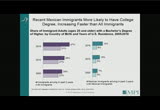

occupations. now, another thing that i wanted to highlight in this graph specifically is this, the difference between 32% of all immigrants and 12% of mexicans who work in what we call professional service occupations. now, again, these numbers show that mexicans are not necessarily in this occupation, but what the number is it going to show, in this slide there's a substantial number of mexicans working in this sector. mexican population, the mexican immigrants are the second largest group after india in working in certain professional service occupations. again, this is something that the ambassador referred to earlier in his remarks. and the reason why this matters is because mexicans are now, even though they're educational attainment has been lower in the past are now beginning to catch up with the other countries. what this slide shows is on the left it shows you the purple

9:57 am

bars that talk about all immigrants annen 0 the right the mexican population. i made a specific look at the mexican migrants in total and those recent migrants who entered in the past five years. why it's important, you can see a trend american all mexican immigrants that show more of the recent migrants are having more college education than before. you can see them in 2005, mexican population in total 5% had a college degree or more, that was 7% for those who had come in the last five years and now looking in 2010, the number of mexican education attainment instead of saying the same in 2010, increased with the flows. and 2016, 14% of people who come in the last five years, 2012 forward had a college degree or more.

9:58 am

this is compared to 47% of course by all immigrants in the united states. but what these numbers don't really show is that the i am crease from 10 to 14% is actually higher percent increase from 38% to 47% in the category. so these are key to note. one of the key ideas is that mexican migration is not only decreasing, but becoming more educated. something i'm sure we'll bring up in other sections. and the mexican population is settled in the united states. 89% of mexican immigrants have been in the united states at least since 2009. that's 89% of mexican immigrants in the united states have been in the u.s. since 2009. the population of mexicans that has come since then only 11% compared to 21% for the other

9:59 am

groups. and i guess, that was-- you can see that there. now another key piece that i'm sure we have received more attention in the media currently is the idea of how many mexican immigrants are undocumented or unauthorized in the united states. this is important to note as the ambassador was noting, in 2007 6.9 million mexicans were here illegally. and this is a difference of 5.9 million in 2016. 6.9 in 2007 compared to 5.9 in 2016. and the makeup is important to note that not all, and in fact, only the majority of mexican immigrants in the united states are really present. some are naturallized and 32% lawfully permanent residents in the united states or have another legal background. this is the idea not all

10:00 am

mexican immigrants are here unlawfully or illegally. only 45% are here in that status. now another thing that may not be surprising, but it's important to note here is that most mexicans who obtain green cards do family reunification channels. in fiscal year, 171,000 mexicans who became lawful permanent candidates did so either through immediate relatives or other family members in the united states, a much higher share than new lpr's. and mexican immigrants were less likely to obtain green cards through the path ways, 2%. compared to the overall population of 12%. ..

10:01 am

this is different or compared to 64% of salvadorans. picking up a set of honduras, 50% resilient and so forth and so on. the key thing twilight is the daca program is predominantly occupied or used by mexican immigrants, mexicans represent 80% of the 700,000 daca hundred thousand daca holders in the united states. 80% of the 700,000 daca holders are from mexico. no with a country of origin makes it more than 4%. it's 80% mexican. researchers have documented the impact daca has on immigrants allies, increasing their well-being, for about providing access to employment, access to

10:02 am

financial stability, access to better and more skilled higher jobs, increase in income, the privy council access. specifically for women migrants who are, many of them mexican of course. so i will leave that there. i think we can go back to other questions, but that's it for now. [applause] >> thank you, ariel. the data give a good base for conversation moving forward and present an interesting profile and some new and surprising in sideways trends of the mexican population. mark will give us context for these, showing as new interesting data of mexicans both in the united states and in mexico, their perceptions of life in the united states, opportunities and how that shapes the thinking about migration. >> thank you. what you like me to do it from there? >> if you want to.

10:03 am

>> good morning, everybody. at the pew research and we've been doing a lot of surveys both in mexico and in the united states of mexican adults in mexico but also of u.s. latinos in the united states which of course mexicans and mexican immigrants make up a large chair. i want to share findings with some of the recent work we've done. much of this comes from 2018. this is a pretty recent date if i i want to give you a sense of what to mexicans think of the united states and particularly about life in the united states. i i also wanted to show you what do mexican immigrants in the u.s. think about life in the united states, and with the do it again if they could? what did he think about opportunity for the kids? what about opportunity over all courts have we seen a change in their opinions about the u.s. in recent years?

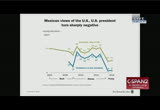

10:04 am

i want to start with mexico first. this is a chart that shows you over time that use mexicans about of the u.s. this is a share, the green light as a share that have a favorable view of the united states. you can see when president trump became president the share of mexican adults are sent at a favorable view of the u.s. dropped from about two-thirds in the last year of obama to in 201730% and we're still at around the same number for 2018. this is this is a pattern that e seen happen around the world. mexico is not unique in this perspective. you can see mexicans have a lot of confidence in the u.s. president. that particularly with regard to donald trump just 6% of mexican adults in 2018 unchanged from 2017. say that confidence in president trump. obama's user interesting because you can see the rebuilding and both measures during the obama

10:05 am

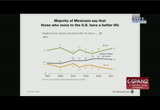

years, and president trump is until the president who set a low level of confidence among mexicans. in the last few years of bush those relatively low level of confidence in president bush at the time. these numbers do change, move around at other times to reflect various events happening in the u.s. the decline around 2010 was right around the time arizona had introduced s.b. 1070. there was come if you look at the data from 2010 you will notice that for arizona did this doesn't much more positive view of the united states, then we were in the field when this happened after the view of this was substantially lower as a result. some interesting findings about just what mexicans think about the u.s. of course we been asking mexicans that whether or not life is better for those of moved to the u.s. they are, or whether there's really not all that different from mexico are whether life is worse for those who moved there. you can see the answer to the

10:06 am

question, people from the country moved to the u.s. have better life, that shares has risen in the last year or so. this is only through 2017. we don't have 2018 numbers yet but even so there's a growing share of mexicans who see like this better for those who have left mexico for the u.s. this is in contrast to the decline we saw for a few years in the last few years of the obama administration. this number has moved around some but note it's down to 10% in 2017. stay tuned, plaintiff some results for 2018 so stay tuned. that's coming. i also want to give you a sense of how many mexicans would like to come to the u.s. if they could. this this is a number we been following for some time. there's been a decline in the share his second like to work and live in the united states. that share is down to about 32%. that was at was at a high of almost 35, 36% in 2011.

10:07 am

the share the say they would do so without authorization has dropped sharply. many mexicans say they would like to move if they could. if they had the means to do so, a woodlake mexico for the united states. but the share who say they would do so without authorization is low today than it was just a few years ago. this speaks to the changing nature of mexican migration, who was deciding to potentially leave and how might they choose to leave. there's a number of different trends going on that are reflected in this particular finding. the view from mexico is very interesting. we want to know about mexican immigrants in the united states and a couple of additional facts of mexican immigrants. as ariel pointed out the number of new arrivals to the united states for years, for four decades, was dominated by new arrivals from mexico.

10:08 am

about 2010, 2011 mexican migration has been dropping for some time and india and china were then the largest single senders a a new migrants to the united states. it's important to note that a want to stress it's not india and china have searched. they have slowly been rising for a number of years. it's that mexican new arrivals dropped sharply, dropped precipitously all the way since the great recession until today. they give you some sense of this, china and any mighty city but one of 50,000 new arrivals in a given year, mexico is not far behind, about 110, maybe 120,000. there are still new mexican immigrants coming to the united states. when you take a look at the attitudes of mexican immigrants and we did a survey recently of the u.s. hispanic population, here is important findings. i want to show you mexican immigrants particularly have

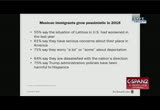

10:09 am

become more pessimistic but thinks in the united states, about life in use, and they are worried about a number of things. first, more than half say the situation of latinos in the united states has worsened in the last year. i comparison among all hispanics only 49% say that. mexican and the goods are more likely to say things have gotten worse for the group. -- mexican immigrants. this is a number that is much higher than it is for the general hispanic public, only 52% of all of all hispanics say the same thing. mexicans and mexican immigrants were in the country without authorization or maybe don't have citizenship, they are the ones with the most concerned about the place in america. 71% say they worry that they themselves, a family member or friend could potentially be deported. this number for all hispanics is 55%.

10:10 am

mexican immigrants are more concerned about deportation that of the groups of hispanics. 64% say they are dissatisfied with weighty things are going in the just today. for all hispanics it's about the same, 65%. hispanics generally have turned sour in the direction of the u.s. over all. 75% mexican immigrants say the trump administration's policies have been harmful to the hispanics. that is higher than it is for all hispanics, 67% say the same. as you can see somewhat of a sense of pessimism, going sense of pessimism, concerned about the direction of the united states, about their own place in america, there's a lot of pessimism in this particular survey. we did ask mexican immigrants and all immigrants either way if you could do it again, would you come to the u.s. all over again? 82% in 2011 and about 80% fall

10:11 am

hispanics and, yes, i would do it again. that number is down to 70% in 2018. you see the decline in the share of mexicans who say do do it again. largely more recent arrivals are the ones who are most likely to say no, i wouldn't do it again if i had a choice. i want to stress the mexican immigrant population is largely settled. many of these folks are not recent arrivals or change their minds. these are often the people of been here for ten or 20 years. this is not just a new arrival story. what about how they see the united states? this is also from our 2018 survey. 85% of immigrants, mexican immigrants, say opportunity is better in the united states that it is in mexico. this is little change from 2011. what about conditions for raising children? three-quarters of mexican immigrants cfius is the better

10:12 am

place than mexico and this is little change from the past. one intent to migrate might be changing, the view of the united states as a place to live for opportunity and for raising children is little change. this is true by the way of all hispanic immigrants. this is not just a mexican immigrant story. there's been an outflow of mexican immigrants from the u.s. to mexico. if you look at data sources from the u.s. from mexico, this chart shows over a certain time number of mexicans coming to the united states at the number of mexicans leaving. you can see the orange bar is a yes to mexico flu and you can see between 2009-2014 more mexicans left then came to the u.s.

10:13 am

the number of mexican immigrants living in the united states has been in decline for some time so this story of mexican outmigration is a story people deciding to return home. you look at mexican survey data as to why people have returned home the biggest reason is to be with family. about two-thirds return dates be with family. maybe 15% say they were deported but the biggest reason is to return home. many of returning late in life. they decide to go after being envious for many years and perhaps to such a quote-unquote retire i'm moving back home and also to be with family. this is an interesting part of the story with regards to mexicans because when we talkedk about mexicans and your citizenship, mexicans have the lowest naturalization rate in the united states of any immigrant group. by our estimate about 42% of mexican immigrants who are eligible to naturalists have

10:14 am

done so. but for all of the groups of immigrants the number was more about 74%. the other interesting story about mexican immigrants is that many who can become your citizens actually haven't done so. and they been in the united states for 20 or so years, maybe more, still haven't become a u.s. citizen. it's an interesting question because as ariel pointed at with his pie chart showing to the legal status, you saw there was a large chunk of people who are lpr is. while many to become a u.s. citizen, frankly there are millions who haven't done so yet. we've asked in some of our surveys why hasn't that happened. here's the fine before mexican immigrants and why haven't havy decided to become a u.s. citizen yet. by the way for about 90% city want to to become a u.s. citizen id that is interesting because it's true not everybody who comes to the u.s. as an immigrant is this really wants to be a u.s. citizen to people,

10:15 am

for various reasons and some people will choose to go home after a two years and never achieve u.s. citizenship or never apply for. why do mexican immigrants tell us they have applied yet for citizenship? language barriers is one of the big barriers. they're worried about the test in english. some of them say they haven't tried yet or they were told that just not interested what you think is quite interesting. financial barriers. his extensive to apply. about 8% of the time we did the survey said they were currently applying for citizenship. there's a multitude of reasons why people might not have done this just yet and if you follow the work of the latino vote you would know in 2060 the were lots of efforts to get people to naturalists so they could vote. it's no surprise there's a focus on that group because it's such a large population of people are eligible to do it right now and many of them just haven't done

10:16 am

so. there's a lot more to talk about with regard to mexican immigration and i look forward to our conversation terms of questions that i will stop there and look forward to having this conversation. thank you. [applause] i'm going to start up with a few questions and then we'll turn to the audience and tv chance to ask yours as well. i want to ask you first, you both showed the declining immigration from mexico and the stock of the population has declined to give mention some of the reasons people may be returning from the united states back to mexico but could you say both the bit more but about whe the reasons why the inflows are down? impassive to mention immigration enforcement but what are some of the other factors that may be shaping to destroyed? >> one of the big factors that the ambassador, ambassador mentioned to the big ones which is u.s. enforcement, the border,

10:17 am

mexico is change. it's a different contradict the terms of opportunities but as ariel pointed out it's also a country whose demographics have changed. when we talk about the potential for migration from a placed, how many young people are there? how many young people who don't have a job might be looking for opportunities? as maximus changed, its economy has improved, can people have opportunities within the country. you talk to young people and they will say they want to become an engineer and decide to stay in mexico rather than go into the united states. it's interesting that demographic of the country are changing. in mexico by the what is aging just like the rest of the world and at some point in the coming decades it will have a higher being aged then the united states. we will see what happens. that's an important part of the story. >> if i can add just one thing. i think in terms of the anthology is one of the things that often doesn't get mentioned is that the also different changes in no mexican migrants

10:18 am

had to send come to the united states. the question you about legally come to the u.s. or not coming illegal to the current is very important to get way to come to the us has become expensive, more dangerous that only because of the circumstances here but because of circumstances and mexico. violence is high in certain border states and border towns which is made a difficult for micros to make a decision others are also more expensive. that's one thing to be for sure to include your conscience of the other factors, i think education has been keeper mexico for a long time has focused on primary level education, has been doing better now in secondary education of which is given more opportunities for younger people to see if they can see in the country of origin. this is by no means perfect. we must understand even if there'll doesn't increase economic opportunities in mexico, there's a lot of opportunities in the informal labor market which cannot provide a full filled wage and in a long-term compared to the united states is still not a

10:19 am

better option. you have mixed factors on one oe one hand, you want to stress economic factors, and mexico that it made things better. >> market, your data show kind of conundrum in a way that people are puzzled the people see the united states is a less, they may have less opportunities. they are more worried about immigration enforcement. they think the situation for latinos or immigrants has worsen over time. at the same time the people said the u.s. has a lot of opportunity it's a better place as were economic opportunity here we known fact our economy is booming, we've really strong job growth. i'm curious if you thoughts about how is this going to play out if people perceive a harsh climate and tough policies but it also see the opportunity for jobs. what does that apply for what we could expect for future migration trip? >> a great question. in the survey we did, we did get

10:20 am

this interesting pattern of responses. on the one hand, immediately many with you to see things have gotten worse and the say the trump administration policies are hurting latinas. they are tying it to the current administration. when looking to the future on many different pieces you see latinos saying the believe in the united states or they see opportunity in the u.s. still but i would caution that the optimism that we used to sit among latinos has somewhat diminished. mexicans are no different in this particular survey. we would ask you think your children would be better off than you were in the future? in the past about three-quarters used to say yes. in this current say that only have to do. that's true of republican hispanics, chair of democratic come hispanic democrats. it's true of mexicans, cubans, every group has had this decline of about 25 percentage points in

10:21 am

this year that expect the kids to be better off. i want to follow up to see whether or not this feeling continues. one other addition, when it comes to their own finances many latinos tells things have gotten worse and they don't expect it to improve. that's counter to the lower an appointment might we are latino workers is at a a record low ad when it comes to a household income, it has risen fast of any of the group in the last year or so according to the census bureau. this sense of environment of what's happening and the connection to the trump administration is something that's reflected in some of these responses in our survey. the pessimism reflects the general pessimism about the u.s. >> i have tons of questions but i like to open it up to all of you and see if anyone in the audience has a question. >> mark, i was interested in your results from the mexican

10:22 am

survey. our surveys over years. i was just wondering if you have done additional analysis on the response from traditional sending regions of mexico to know whether those regions in particular have any trends that would be of interest to us? >> that's a great question or the service are about a sample size of about 1000 per year. it's hard to do a more detailed regional analysis. we don't have that in this particular set of service. we do have a lot of surveys now so we do have a large sample size. it would be interesting to take a look at this and i hope we can do would say there are differences in attitudes above yes, how close you are to the u.s. border if you within 400 miles of u.s. border in mexico, you have a more favorable view that if you're farther away. which is interesting because on the u.s. side americans who live closest to the border have a less favorable view of mexico

10:23 am

but farther way they have a more favorable view of mexico. there are some interesting differences regionally. >> other questions? >> office of immigration statistics. the 31% who are not interested or just have not apply for citizenship yet, could you talk more about some of the major reasons within a category? >> that something, it's a great question. in our 2015 survey we had asked immigrants who were in the country legally, in other words, they have a green card that toe achieved citizenship yet, we asked them a series of questions and you saw the open-ended question on this one and it was an open-ended question. so many responses it's hard for me to remember all the particular specifics and i can point you to the top line for that. but these categorizations

10:24 am

generally reflect this one category. many people said they just were not interested. that was an important part. other, the other component was also a lot of responses but i don't member all the details specifically. i had to get back to you. i be happy to send you the top line. >> other questions? >> my name is mary gardner. and with the u.s. hispanic chamber of commerce. i had asked his question because it is voting day. i'm wondering if anyone had information about the political affiliation of mexican immigrants in the united states that have naturalized or which policy issues are most motivating to that community of immigrants? >> in some of our work we then we looked at the political affiliations of mexicans and mexican immigrants. very strongly that didn't buy with or lean towards the democratic party.

10:25 am

one of the big drivers of that general statistic for the hispanic population overall and that one of the more strongly leaning democratic party groups. when it comes to policy issues, the issues they tend to point to our economics, healthcare and education. immigration is an issue more so than it is for the general u.s. public but again because mexicans and mexican immigrants such a large part of the population they are driving the results generally for the hispanic population. this year i will say that when change we did see is immigration is now seen as one of the top issues facing the country, just equal to the economy. something that is reflected for the general u.s. public is also it's not unique to hispanics but is something we saw in the survey. thank you. >> any others?

10:26 am

10:30 am

>> we have an answer. can we -- let's speak to english just in case anyone -- >> my name is alexander. i will speak on the panel later but i think it's important to contextualize it in relation to the conditions of the whole family. it's the children who are citizens here or who are broader a young age and are doing better educationally. don't have necessarily the support systems they need at home because their parents may have undocumented status or a different kind of precarious status the forces them to be working three jobs and living and precarious conditions and, therefore, they can't support the children in the way of immigrant families can support them and i think that affects significantly their aspirations

10:31 am

as well as the financial support and other resources they need in order to be able to complete high school and college. they end up working as well while they're studying and that puts an end very difficult conditions in terms of completing their studies with the same kind of support system that other groups might have. >> let me address the -- [speaking spanish] [speaking spanish] [speaking spanish]

10:32 am

10:33 am

conversations][inaudible conversations] conversations][inaudible >> while we are waiting, i'll go to start making introductions. he's emigrating. he will be back soon. so first on this panel we have ramiro cavazos, president and ceo of the u.s. hispanic chamber of commerce. with his great expertise and he

10:34 am

served as director of economic development for the city of san antonio among other positions. next we have fay berman, a mexican-american writer who chronicles the cultural and political life of the hispanic community and used her current work is published in a variety of mexican publications concern which are read from across the hispanic speaking world. her book "mexamerica" was awarded the international latino book award in 2018 and finally mario hernandez will be our moderator today turkey is the director of public affairs at western union and he's responsible for the development of public affairs strategies to reach western union is various constituencies in the u.s., mexico, central america and of the caribbean. so with that we will start. thanks. >> great. excellent. good morning. buenos dias. again, my name is mario hernandez. i work for western union, and

10:35 am

one of the things i like a lot about my job is the opportunity to meet a lot of immigrants across the united states in traditional receiving cities like los angeles, chicago, houston. but also in merging receiving communities like nashville, tennessee, like places in north carolina, south carolina, et cetera. and for me this issue is very important, and to think a little bit personal because i am an immigrant myself. i was born in talks -- pascoe, mexico. thanks for the education here i became a u.s. citizen is recently, so i am really proud new american.

10:36 am

and i like the opportunities this country offers to immigrants. and right now there is an opportunity to precisely talk about the contributions of mexican immigrants. i really like the presentation, the previous presentation that provide us the contacts for this. but now we're going to talk about people of -- the real immigrants, that's why we have two super analysts here and we will start with a period -- start with say. >> more than a decade ago i was writing about music and dancing new york, and i was seeing the enormous change in new york becoming -- i couldn't lose that opportunity. what i was seeing portrayed in media, and what i was seeing

10:37 am

with my eyes, were very different situations. new york, like many other metropolitan areas in this country, has two mexico's represented. these elite, the cultural, economic, intellectual elite, artistic elite, and also the very poor ones. in new york it's very dramatic because most of the population is from -- very poor, and also you have superstars that arrived to this country because they want to have a universal projection. it turns out this is now the biggest empire in the universe for the time being. so i started writing about that reality, and what i called

10:38 am

"mexamerica," talks about a multifaceted, animated, effervescent identity that i believe destroys the prejudices and the stereotypes that were made about the mexican the aspera. so i i taught in the book about the contributions of mexicans, mexican immigrants, and sometimes, although that's a small part of my book, of the following generation of people of mexican origin in the art, in science, in technology come in academia, in business, in diplomacy and in politics. that's one of the themes of five themes in the book. i also speak about language and i realize touring with the book that a great percentage of the

10:39 am

mexican origin population doesn't speak spanish any longer, to my amazement. so i have to come up with -- the main idea was to show that we are much more the remittances and folklore. we are very appreciated for our tequila, our sink at a mile, our marriott use but there's so much more. before i share the contributions of this remarkable people that i put in a book which are slim examples of who we are, i want to underline that them "mexamerica" cultures in the proofreader to its invisible. it doesn't exist in mexico. it doesn't exist in the united states. why? one thing is, although the contributions of remarkable mexicans and "mexamerica" are recognized, we did see them as

10:40 am

representative of a document. number two, is justifiably the attention is on the undocumented. however, a narrative, the undocumented -- how many are undocumented of the mexican the aspera? -- the aspera. that would be like -- [inaudible] okay. so that's a small part, insignificant but not the most important part. and when you open a newspaper in us-40 mexico, what you see. the border, drugs, the undocumented, and it's never about this 36.5 million people who are here for decades and

10:41 am

decades and to contribute to the society. another thing is there's stubborn -- that mexicans or mexican origin americans are mexicans. nothing happens to the on the journey. nothing happened to them by immigration. nothing happened to them by being ten or 20 or 30 years in chicago, los angeles. they speak spanglish but the identical to the cousins. there is no merchant, , mexican and american culture. as if the population of mexican origin lives isolated from european american, asian american african-american, american jews. those are the main reasons. now let me go to this people which is, you know, i think i

10:42 am

only touched in a few people because i live in new york, i'm a freelancer, the sample is i think probably very small compared to the reality. and i start with the arts because i think the impact of mexican art in the u.s. has been enormous. diplomats like talking about it as soft -- give me -- soft power. i don't think it is a soft power. i think it is one of the most powerful sources of who we are. the mexican culture is very strong when it comes to its art. i did know anything about it when it came to this country. he was, he came during -- he immigrated to the united states, became of his own right of vanguard, well-respected artist

10:43 am

but one of the main things he did -- [inaudible] is that he brought the work of picasso, to the united states. which meant come this meant the beginning of modern art in this country. how the capital of modern art changed from paris to new york. magill -- before he was very important in all the arts of mexico, before he was an important anthropologist and before his research in bali, he came for about ten or 12 years to new york. he had a very important -- he made illustrations that portrayed the elite and the

10:44 am

celebrities of this country and a very peculiar way and the covers of "vanity fair" and the new yorker. he then was fascinated by african american harlem which was, you know, the birth of the jazz, charleston, lindy hop, the blues. at the white population had no clue about the picky was the first that portrayed it in illustrations. edifact he was copied throughout the world and they became emblematic of what harlem was supposed to look like. another important contribution was that the organizer of the most important exhibits. it was called 20 centuries of mexican art. another important thing is he brought together all kinds of artists that together created what we now call modern art.

10:45 am

copeland, martha, eugene o'neill, who else? et cetera, et cetera. so he was an important element in the birth of modern art in this country. and, of course, in mexico, too. and then of course we have fingerless who left minerals all over this country. but not only that, they were -- murals. for example, jackson pollock was a student. george real was a student. these were the people that make the first murals in this country, no?

10:46 am

not jackson pollock. jackson pollock is no for something else. then we have characters in the present like julio -- who converted neighborhood museum that was dedicated to marginalize puerto rican art, and one of the most important institutions dedicated to the promotion of latin american art and hispanic american art. but also underline the importance of all this that i told you so far about this artist i learned from him. the importance of this artist they came from latin america on the birth of modern art in the united states. and there is josé that probably a lot of people don't know about because dance is a forgotten art, but he was one of the pioneers of modern dance in this

10:47 am

country. he came from -- because of the revolution. he really, the role of males in dance really owes a lot to him. he was also quite important in portraying narratives through dance, using the body as an expressive force, which sounds like a natural thing but it's not really the case. and what's interesting is usually dealt with universal themes but also and often with mexican things, chapters in mexican history or traditions, for example, another, we have a lot of choreographers of mexico in the united states, especially new york. one that comes to mind to me is

10:48 am

hobby our -- have your -- [inaudible] which means moon jag wire serpent. he's originally from a town in the jungle of -- and he was trained so he is able to transform himself into an animal physically or spiritually, his words. but basically he puts on stage the story or this transformational being a migrant into a citizen of new york. it's quite fascinating as you know an immigrant, as an artist, for anybody to see. and then we have our musicians which there are tons. carlos chavez made his most original universal and mexican work in new york.

10:49 am

he was a very good friend to -- they spoke about classical music of the americas, to transform, to get away from the european romanticism to create a modern not nationalistic music but something that contains something that was specific to the new world. and we have tons of composers today. i juilliard -- going to look at notes. the head of the school of music, to have the quartet latin america, four brothers come one of them is here that they really introduced to the world contemporary latin american music. you would have to read the book to find out why all this happened, and we have of course

10:50 am

the three amigos in film, of course in journalism we have jorge ramos, et cetera, et cetera. but we also have people in other areas. for example, in medicine we have a bunch of doctors pick an interesting story is the one of doctor q, now producing a movie about his life. he started as -- [inaudible] >> we can continue this later. i think the opportunity now for romero. >> thank you, fay. [speaking spanish]

10:51 am

[speaking spanish] i'm very honored that our ambassador who spent many, whose home is still in san antonio has served both nations. i myself work in washington. my hope is in san antonio and i sleep on planes. i just wanted to say that i will do my best to give you a sense of the mexican experience in two parts. the first is my own personal story. my family in texas, and the second part will be more the historical perspective of what mexicans have experienced in the u.s., even though they were here before he became the u.s. and so when we use the word immigrant or migrant, although each usually attributed to

10:52 am

mexicans, it's really not accurate. the japanese have a saying that when you drink the water you need to remember who dug the well. and so for me perspective is so important. the first part and i will do this within ten minutes, i promise, and then open it up to questions, is my story. i can trace my personal story to my family to 1628. this is this is not the "grapes of wrath" story for the rest of the mollis story. but my father is a sixth generation texan and he was born in a small town of -- those of you that no taxes, it's ten miles from the mexican border. it's a small ranching community. my dad was a descendent of el capitan who came from spain and settled in monterey, northern mexico in what is now south texas and northern mexico.

10:53 am

he came to serve in spain as a young adult. he entered in 1628, and those days became the state of -- where monterey is today. he married in 1630. we love ancestry in my family wanted to forget where we came from. and boy, , did we get to figuret out. for more than a century after the spanish came here they didn't go north of the rio grande because in those days there were many native americans and the spanish did not move, nor the mexicans egos of the stairs warriors at that time who did not want to give up the lanes. give it up for speculate of why that's important. at the time these are all invaders. in the 1700s spain to subdivide the land north of the rio grande in texas into large land grants.

10:54 am

there was no risk to the spanish, but it was a hazardous risk to the people living there. in 1781 josé, my ancestor, my fathers grandfather can receive 600,000 acres because the spanish land-grant with 90 head of cattle. it's in what today is kingsville, the king ranch and it was a vast acreage and at time the stone as san juan. during those years that followed the cavazos families as most families in those days, they were pretty prolific. that ten, 12, 14 kids. so over the years they lived under the crown of spain picked the nation spain, mexico, the republic of texas, the u.s., the confederacy, the south and again the united states. josé cavazos received the largest land-grant in that area and it's now known as -- over the years the land-grant was divided by the family and we still have a little bit of

10:55 am

property over years they sold it or it was lost or traded off as of the parts were given up. my grandfather was born in 1890 and help out a small town. my dads first cousin was the first cabinet level appointee appointed by ronald reagan in 1988 as secretary of education, the first latino in the history of the u.s., and he was president at texas tech university, and then richard cavazos, his brother, was a retired 4-star general who was the highest-ranking latino of mexican heritage to achieve that rank. so let me give you the story of why we are here today. a friend of mine drafted piece that he called mexicans didn't immigrate to america. we've always been here.

10:56 am

i mention i can trace my ancestry to 1628 but if i run down the street and someone asked me what your name, i would imagine if that person resides in the white house he might question my heritage. so we have lived in the u.s. before it was the u.s., and, quite frankly, we are not going away. the chatter of building a wall is very disappointing. more than anything it is insulting and these accusations that mexicans are criminals or rate this is really unfair. these centers long record of anti-mexican sentiment has really affected the question, is ascendancy and achievement, special people overtime keep pushing you down, that we will persevere. i'm an optimist, and i know that we are going, as fay imagine, this is a very proud group of

10:57 am

people. but in the early 1800s 1800s expansionism in this country was fueled by the phrase manifest destiny. as you all know by now i love history. the u.s. wanted to go to the pacific ocean and hit asia. guess was in the way. mexico was inconvenient in the way. the u.s. invaded and the treaty of guadalupe a integral to the mexican american war in 1848 but guess what mexico lost. texas, new mexico, california, nevada, utah, wyoming tribune spicules inherited hundreds of thousands of native americans and millions of mexicans who had long lived on the land. the u.s. army responded by data with the native americans by walking them 450 most eastern new mexico and many of them died before they were sent back to what war internment camps or reservations as they're called today with beautiful casinos. data with a much larger group of mexicans, many of our ancestors

10:58 am

were landowners, officeholders, entrepreneurs, lawyers, bankers and members of the clergy with more complex and it relates to my story earlier of achievement. the government could not assign mexicans to reservations. our customs, our language and traditions and values, our food color committees have all become part of america is today. we are a nation that is already very mexican, whether the u.s. government has liked it over the years are not pick still the u.s. government has done its best to make these citizens, foreigners come in the own land and made him feel unwelcome in their own country over the years. congress passed in 1862 the homestead act allowing americans once they had passage to the west, the manifest destiny, to apply for western land in exchange for forming it. guess who took the land from it.

10:59 am

they took it from the mexicans who would already lived there. but laws and even the way those laws were trumpeted, , if they were written in spanish and the folks and control said only a genuine contracts can be in english, then that contract is no longer legal. during the great depression many of you know that the u.s. deported 2 million mexicans. more than half of those were u.s. citizens. they were devoted to a country that they did not know. so the history of bigotry, discrimination and exclusion doesn't mean anything. we are still here. they are seeking to close the stable door a century and a half later after the horses had bold as to say in texas. and so we are a part of america's fabric and society. latinos today contribute

11:00 am

$1.5 trillion in purchasing power where the tenth largest economy in the world. latinos, this relates to the u.s., hispanic chamber of commerce, my day-to-day work, this is why i'm an optimist because we control the future workforce of this country. we control the future of vendors and people do business in this country and we also obviously are the largest and fastest-growing consumer base for this country. .. we're not consigned to our ancestral geography in the great southwest. the fastest growing latino communities today are north

11:01 am

dakota, alabama, georgia, pennsylvania, louisiana, south dakota and utah. there's a reason why montana is named montana, because mexicans live there, too. it's really montana. mexicans are here in our homestead, in homeland, to say 33 million latinos have been born in the u.s. a fence will only keep us in, not keep us out. so i just wanted to conclude by sharing with you that as we look to the future and open it up to questions, 80% of the daca recipients are mexican. two out of every three hispanics in the u.s. is mexican, and of the three richest people in the world, two of them are latino. and the last thing i want to point out is the economic development relates to our future and mexicans that live abroad, both in the u.s. and elsewhere, send more than $30

11:02 am

billion back to mexico, and it is about economic development that immigration from mexico has actually gone in reverse. more people, americans are moving to mexico than are moving from mexico here. with that, i just want to thank everyone for your faith and your optimism. today is election day, and we need to go out to vote. >> thank you very much. [ applause ] >> i have some questions for you. however, we are kind of short on time so i will go straight to the questions from the audience. if there are any questions, please raise your hand and there is a microphone there. >> thanks. i get to start the questioning round. i was just curious to hear the panel's impressions, i'm also from texas and i think there are few non-mexican latinos there

11:03 am

who haven't been insulted by being called mexican, not because being called mexican is insulting, but i think it's not pleasant to be called something that you're not and not to be treated like an individual. however, i think it goes the other way as well. so mexicans in the united states, the impressions of other latino groups, particularly countries of the northern triangle, immigrants from those countries, do affect how people are perceiving all latinos in thend and of course, mexicans being the bulk of them. so i wonder if you have any thoughts to share on, you know, as the first panel went into, you know, how mexican immigrants in the united states are becoming more diversified and of course, there are many accomplishments of mexican immigrants and mexican americans, but do you have any thoughts to share on how to -- how the community can sort of distance itself from these other

11:04 am

groups, if that's even beneficial to anyone? thanks. >> i think, you know, in places like new york or l.a., especially new york, where mexicans are a minority within hispanics. not for long, but it's been very convenient, the label of latino. i think we use it whenever it's convenient and whenever it's not convenient, no, and sometimes it's harmful. you know, for example, speaking about the latino voice, people say why is not the main concern immigration? well, for some people, it's not. cuban americans have other concerns. puerto rican americans have other concerns. so i think when you're in texas, i was in texas last week, and also, i think three kilometers

11:05 am

out of austin it would be a different world, because everybody has their beto teeshirt. if you didn't have one, it's because you had a sweater on. it's very mexican american and it's very close to the border, and you go to other places, you go to miami or you go to new york, the reality of the latinos is different. also, for example, the label chica, you say to somebody of mexican origin in new york, basically mexican, because we are mainly immigrants, your chicano culture, i don't recognize it in myself because i don't belong to that history, that time period, but in texas, sometimes it's synonymous with mexican american. so that's my answer.

11:06 am

>> the only thing i would add to that is that remember a gentleman who used to be a ceo in the late '80s, he said something that stayed with me forever. it's that being hispanic is a state of mind. when you think about it, latinos are hispanic, it's not a race. i mean, we could be cameron diaz and be part cuban and blond-haired, blue-eyed. you could be brazilian and speak portuguese and be dark-skinned and beautiful, and you could be asian and latino if you are filipino and speaking tagalog and all of us who form this whether it's chicano or hispanic or latino or mexicano or tejano or whatever we call ourselves. i meet a lot of latinos today who don't care that they have

11:07 am

been given a label. they could be somebody named morgan rodriguez and they may have lost their spanish, but they are part of that diversity in being american now, and i think at a certain point, as we move forward, we won't have as many labels as we have today, because i think labels tend to be counterproductive. so anybody wants to be latino, you're welcome to be. >> we have a question. >> as a non-mexican latina, i think that the good thing is that -- and we have to be very careful how we divide ourselves. because at the end, we are more similar than not, right? we are all immigrants and we are all the others, to put it somehow. i think there's a lot more in common in that experience than even where you come from

11:08 am

sometimes. so i think we have to be careful about dividing more instead of bringing together, because there's a lot of fights we have to face together. >> i have a question for you. >> yes, sir. >> you are a seventh generation texan, and your personal history is really fascinating. i think that providing all this information -- >> [ inaudible ]. >> oh, yeah. very, very, very interesting. we need to know more, because especially in this environment. it is difficult to have precisely the recognition, the knowledge, what we can do to promote -- for example, you say in your book that mexamericanos

11:09 am

are misunderstood even in mexico. how can we increase understanding of the mexican american community and how can we have a better communication with seven generations and recent arrivals? >> the only thing i would say that is, whether you are first or seventh generation, thinking like an immigrant is the mindset that my family has maintained even after having been here so long. they still are very passionate about being latino and they feel as was stated earlier that we're all together in this, whether we're cuban or puerto rican or colombian or venezuelan or seventh generation or first generation mexican. it really doesn't matter. i think that we should not allow anyone to divide us, that we need to be united.

11:10 am

that's why i'm very excited to be the ceo of the united states hispanic chamber of commerce, because the worst kind of discrimination i think is financial or economic discrimination. it's the color green. it's the companies that i represent that don't get contracts with the u.s. department of defense and that's the largest buying service in the world. so for me, if we are going to be successful, it's through education, it's through financial strength, and it's through nafta and it's through agreements that give us as a north american continent the ability to compete in a global economy using mexico, canada and the u.s. as a fantastic economic bridge for our jobs, and our companies. that's why i mentioned carlos slimm and jeff bezos and the 4.7 million small businesses that we represent. that's really our focus. that's where our focus should be, not on whether we're cuban

11:11 am

or mexican or texan or coloradon. it's am i creating jobs, am i creating wealth for my family. we are ready to put us -- my dad had a saying. we just want to be where the action's at. we don't want any limitations. because we are going to compete and win. >> actually, i have a story to tell you. i hope that you know this dream of being integrated happens. however, mexicans have always been second class in this country. and the mexicans themselves don't help. i was speaking a month ago with an important leader of human rights in chicago and he was telling me one of the reasons why things didn't advance was

11:12 am

that everybody wants to take the credit of advancing human rights causes. so this one doesn't want to speak with that one which doesn't want to speak with that one, et cetera. that's problematic. another thing is owning who you are. i was on a panel with writers last week and both of them were dreamers and i'm blond, i look very different than them. we come from a completely different social, educational background. their parents never went to school. one of them said she really suffered that she was not considered a mexican writer. i said precisely, you're not. and she was not happy but she's not. she's a mexamerican. she has nothing to do with the experience of mexico. she has the experience of being a child of an immigrant in this country.

11:13 am

that has been discriminated since the beginning, especially in texas, so i think it's not like dividing yourself but i think to underlie the great successes which i think many groups are doing especially now is very important, because i think there's a lot of stereotypes in this country. it's as if we are all doun undocumented workers, we are all 5'1," we all have a sixth grade education, we are all with this image stuck and i think -- i really think we have to fight that that's not the case because it's not just meeting one person who defies a stereotype. there are so many more, so i think there really has to be a movement and i think there are

11:14 am

many groups, new groups that are really trying to encourage that. >> thank you, fey. you mentioned there are initiatives, and there are many national organizations that are trying to increase this understanding. one of them is the american-mexican association. that is an initiative that is emerging and we will be hearing more from these organizations. i'm part of the steering committee. what they would like to do is enhance the mexican american community here. i think there are probably more questions. however, we reach our time limit, so i would like to thank the wilson center, mexico institute, immigration policy institute, for convening this

11:15 am

11:16 am

panel. i'm the program associate for migration at the mexico institute for the woodrow wilson center. i want to thank everyone again for being here today and bearing with the rain and the election and everything. i think this panel is quite important, given that the data we saw in the first panel of more mexicans returning to mexico now than are actually coming, and with that, i really want to introduce our two panelists here. we have alexandra alonso, chair of global studies at the new school. the current holder of the eugene m. lane professorship for excellence in teaching and mentoring. and second, we have maggie l loraro, she migrated undocumented to the united states with her family at the age of 2. she has been living in mexico for the last decade. in 2014 she contributed her experience to a book which formed into an organization of which she is the co-founder.

11:17 am

with that, we will start with the presentation. >> thank you. thank you for the invitation to participate in this space. i wanted to start talking about what happens in the aftermath of deportation and return. i appreciated everything that i heard in the previous panels, but i think it's important to now focus our direction to what happens in the aftermath of deportation and return. i want to share a little bit, i work at an organization, graa grassroots organization by and for the community that we were born in mexico, grew up in the united states or lived in the u.s., and have been back to mexico, because of deportation, the deportation of our family members, or forced to return which at the end of the day, is also a systemic way of having to leave the country.

11:18 am

i wanted to talk a little bit about our community and of the increasing numbers of deportations that have been occurring to many countries, but in this case, mexico, of people that get deported or people that have to sign voluntary departures which at the end of the day is basically the same thing as being deported, but also, it's important to think about all the people that are returning with the people that get deported. we don't have numbers a lot about that, about all the people that get deported with their families, and it's the policy that we're living now is the policy of separating families. and also, diversity, i think it's very important to talk about the diversity and the people that are returning and being deported. it's important to not categorize only one sort of face of deportation and return. i think it's very important to having consideration the experiences, the places where people are returning within

11:19 am

mexico. i think that's very important. it's not the same thing, returning to mexico city, than returning to guerrero, where people are having to migrate again because of the violence and the situations. it's important to take into consideration the gender, the needs, and also the age is very important. many people are returning who are now 35, 40, and mexico discriminates a lot in terms of the labor and the ages and it makes it hard for people to get inserted in the labor market again in mexico. the language is also very important, the level of education, and the health conditions. as well, what does it mean to return to mexico, or the sort of welcome back to mexico by the government. it's funny, but many of us are undocumented once we arrive to mexico, because it's very difficult to get access to an identity document, and that's something that we have been seeing and we have been talking a lot about. mexico makes it really

11:20 am

complicated to have access to an identity document and it's terrible, because that also -- the rest of the rights get violated because you don't have an identity, so it's more complicated to get access to health, get access to a job, get access to even renting a room or a house or everything. it's very hard. in the terms of mexico city, there are no shelters for people who get deported. people when they get deported after living 20, 30 years in the u.s., arrive and they have to go to the shelters that are for homeless people, and that's not the same profile and many times it makes it a lot more worse for people. the low wages and the poor working conditions is also something that is affecting the families that are returning. in terms of revalidation of u.s. degrees, it's also been very hard in the last years, all the other organizations were part of the changes to the norms which now makes it easier to be able

11:21 am

to revalidate u.s. studies in mexico, but now the biggest challenge is actually implementing. mexico has a lot of nice laws but the challenges to implementing them at the local and state level. the programs in mexico, there really are not many programs that are specifically for the needs of the community. that's been very challenging because they try to insert deportees, returnees, to programs that are already existing but it's very different, the needs again and the profile, so it makes it challenging to get into the programs currently. some of mexicanos, a strategy was implemented by the government. we have seen in the day by day that is not very efficient. there is no followup on cases. they give you pamphlets or flyers or something but there's not a real followup in the process of a person when he gets deported or returned.

11:22 am

also, there needs to be evaluations if the programs are efficient or not, and there isn't, so it's very important to also have that into consideration. there needs to be inter-institutional communication which there isn't among the institutions in mexico, which that makes it also very challenging. i think there need to be political will overall. i think that's the most important thing. and it has to be seen as the experience of deportation and return, not as just something immediate or something that is urgent. we need to receive them, yes, thams importa that's important, but it needs to be seen as a process, long-term process for families and it's not seen that way right now. i think we need to start changing that narrative. although we do accompaniment to people who get deported or they arrive, we have been able to trace different routes to support people to get access to the different identity documents that there are and to have access to health care and even if they need a place to stay, we

11:23 am